Book launch for Danny Licht's "Cooking As Though You Might Cook Again"!

and a conversation Agnes Borinsky about her novel "Sasha Masha"

Dear Friends,

Please join us to celebrate the publication of Danny Licht’s Cooking As Though You Might Cook Again! The book launch will stream live on Wednesday, January 13th, at 3:30 pm PST / 6:30 pm EST. RSVP here!

Danny will read from his book, followed by a short conversation with Rachel Kauder Nalebuff of 3 Hole Press as they sit, socially distanced, around a fire.

Until then, order your copy of the book from our bookshop or via your local independent bookstore. And if you have the book, please send us pictures of your homemade beans, risottos and roast chickens! This has begun to happen naturally, and we welcome more of it.

A Conversation with Agnes

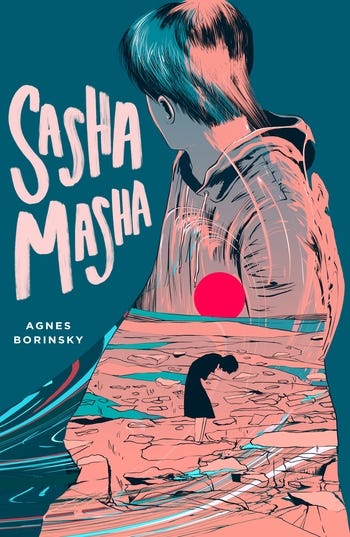

During the quiet of the holidays, we talked with 3 Hole Press author Agnes Borinsky (Brief Chronicle, Books 6-8) about her new book, Sasha Masha (Farrar, Straus and Giroux).

Sasha Masha is a short novel told through the voice of a teenager, as they realize and begin sharing that their name is no longer Alex, but in fact, Sasha Masha. We wish we'd read this book as teenagers—but we also want to say, it's not too late! No matter your age.

Below is the culmination of our conversation with Agnes about her process, the physics of plays versus novels, pets, and learning from our teenage years.

Rachel: I loved how, because Sasha Masha is told through the voice of a teenager unfamiliar with political vocabulary, everything almost had to be described physically. And even though I’d never encountered feelings put to words this way, I related to it so deeply and immediately. How did you manage to write this way?

Agnes: I’m so grateful for this characterization — and glad you felt that way! I don’t think I knew what I was getting into when I started writing this book. Which always helps. I knew I was trying to write about a character who had clarity about a name, but not much else. I don’t think even I, as a writer, had clarity about much else. But I tried to trust what I knew and follow it. Milan Kundera says somewhere that Kafka took scenarios that might seem like jokes and stretched them out, insisted on staying with them for the duration of a novel. That’s kind of what I was trying to do — commit to this seemingly random thing of a name, and let it work on me.

Later I knew that it was a book about gender. And I was trying to delay the inevitable language — trans, genderqueer, GNC — as much as I could. Those words are so important, and also I think we sort of forget what they mean sometimes. It’s too easy for words to take us to the brain, rather than staying in the body. Bodies don’t lie as well as brains do.

Why the world of teenagers?

I mean, this is a little embarrassing to say, but I feel like I’m kinda a teenager all over again, moving through my own gender journey of the last few years. There are the hormones, for one thing. But then there are the waves of petulance and defiance and shame and cluelessness and feeling like a total beginner when it comes to ways of caring for and relating to my body, and presenting myself in the world. So — I’m maybe more of a teenager now than I’d like to admit.

But I also think there’s something worthwhile in casting all these spells and beaming all this love towards my own actual teenage self, that slightly smaller human who didn’t understand a lot, and who is inside me still, somewhere. In the hopes, of course, that some of those spells and some of that love can reach other teenagers, now, who I don’t know. Or the inner teenagers of my fellow “adults.”

Do you have thoughts about YA as a genre? I ask because I want everyone to read this book, and I wonder if having a YA stamp serves a purpose and what the purpose could be. Does it signal that a book guides a reader through a period of growth? And if so… is it strange that we narrow YA readership only to young people….what do you think!

I don’t think that YA books are necessarily any less complex or “real” than non-YA books. There are so many contemporary YA authors who write about the heart in glancing, slippery, subtle ways. Kacen Callender, Lynne Rae Perkins, Alex Gino, Lilliam Rivera, to name just a few, come to mind.

But I do think that there’s a sense of responsibility that comes with the genre. It’s —yeah, just as you say, something about guidance through a period of growth. Like, the responsibility I feel when I am a teacher, or a caretaker of some kind. There’s lots of art I love that is “irresponsible.” But the distinction is also not quite that neat, binary, blah blah blah.

To get back to your question: writing YA forced me to say some things I might otherwise shy away from saying. Simple things, that felt hard to say in the way that simple things can be hard. I’d like to think that YA might be of interest to older people because we’ve all been teenagers. Discovery and growth and hurt and fear and love are all so intense when you’re a teenager — but those feelings don’t go away. They maybe just get muddy. And it can be nice to rinse them off sometimes, get a sort of brightness again.

Characters in the book highlight the importance of queer and artistic ancestors. The list of ancestors at the end of the book does this kind of wild and beautiful formal thing where it blurs your own ancestors with Sasha Masha’s. Could you talk more about this?

I used that word “spell” earlier. And I think that that’s what I wanted to sneak into the book. A glittering and torrential spell of love and protection.

We talk about ritual all the time in theater. Can’t novels be a kind of ritual too?

I loved how in this typical teenage exchange where one friend is recommending a book to another and shocked that the other person hasn’t heard of it, the conversation is all about…. Genet and Our Lady of the Flowers! Are you trying to subliminally suggest a new teenage lexicon? Or did you actually read Genet in high school? You probably did….

Lolll. No, I didn’t read Genet. I think those books would have scared me. I did sort of cluelessly go to a screening of Querelle, though. And was completely overwhelmed and obsessed, while also being completely unsure of what to do with that obsession, where to take it next, why, what it meant. I spent a lot of time in high school going to the movies by myself.

I get the sense that a lot of teenagers today are braver than I was at that age. So maybe there might be room for more Genet…

How does writing a novel feel different than making a play?

Plays always exist in the time of performance. You can speed up or slow down narrative, but you can’t speed up or slow down the time of a play unfolding. That’s what’s thrilling about it.

I struggled with a lot of things when I was writing Sasha Masha, but maybe the hardest adjustment from playwriting to novel-writing was figuring out how to control time. Play time feels thick to me, it’s already there the second you show up with bodies in a room together. Bodies reek of time! In writing this kind of novel, though, basically a representational novel, there are no bodies to start with, just words. So time feels thin. You have to constitute it from scratch, conjuring an unfolding of events, a string of moments, or the opening up of memory within a moment. It’s funny, I’m realizing now that Sasha Masha is a story about a body trying to make itself “heard” in language. Maybe my struggle as a writer is not so far off from my character’s struggle… how to get thickness, the feeling of a body, of time, into language, onto the page.

A press like 3 Hole, of course, kind of upends those distinctions between performance texts and printed books. Daaimah Mubashshir’s play feels more liberated in time than a lot of other performance texts, and also feels deeply embodied. And then there are pieces like More Stupids, that have their own wildly and gorgeously complicated relationship to time and unfolding and the bodies that take them up and use them and become a part of what they are.

An artist I once worked for talked about how our previous works—if there is something in them that is still alive—will be reborn into new ones. There is so much of Brief Chronicle, which is also a coming of age story set in Baltimore, in Sasha Masha. Can you talk about the relationship between the two?

Baltimore is in my body, in my DNA, though I don’t live there, don’t think I want to. Both Brief Chronicle and Sasha Masha opened up for me when I started peering into the corners of my memories of that city I love, feelings I associate with it, with certain streets and restaurants and theaters and parking lots.

And I think that both of them come out of smuggling facets of my adult desire —especially desire that maybe scares me, confuses me, that I don’t know what to do with — into places that I know from the first twenty years or so of my life.

There’s probably something to be said there about constructing a future by re-inhabiting, re-conceiving the past. That’s been on my mind a lot lately with current writing projects. Thinking about religious and cultural traditions we inherit… but it’s true of places, too.

It’s tricky. I know Baltimore is also a real place, now —a changing place. My Baltimore exists in memory. But I’m not a journalist. In Brief Chronicle and Sasha Masha, Baltimore is kind of like a psychic jungle gym where I can perform experiments on my own heart and try and catch whiffs of what’s ahead.

Seeing the world through the eyes of a pet illuminated so much for the characters about non-judgment….What have you learned from the animals in your life? Or is there something else about animals that you’d like to say?

I don’t actually think I have anything profound to say about animals! But maybe that’s just my way of honoring the fact that animals don’t answer interview questions. At least not in any way I have been. I do think animals come up a lot in things I’m writing, and I feel grateful you’ve clocked it. I suspect it has something to do with wanting to remember that there’s always a beyond, always something that just escapes our interpretive eye. In stuff I write animals are always coming into the frame, and then disappearing just past the edge of it.

One day I’d like to live with animals again…

Sasha Masha by Agnes Borinsky (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2020)

Alex feels like he is in the wrong body. His skin feels strange against his bones. And then comes Tracy, who thinks he's adorably awkward, who wants to kiss him, who makes him feel like a Real Boy. But it is not quite enough. Something is missing. As Alex grapples with his identity, he finds himself trying on dresses and swiping on lipstick in the quiet of his bedroom. He meets Andre, a gay boy who is beautiful and unafraid to be who he is. Slowly, Alex begins to realize: maybe his name isn't Alex at all. Maybe it's Sasha Masha.

Wishing you peace in the new year,

3 Hole

3 Hole Press is a home for performance in book form and everyday life. We publish titles that expand our notions of plays, scripts, and scores, how we engage with them, and how we distribute them. We view publishing as a step towards making contemporary performance more accessible, and celebrate performance created for a reader.

In order to keep our titles accessible and events free, we operate through a non-profit model. Our publications are printed through the support of the Literary Arts Emergency Fund, the New York State Council for the Arts, the Brooklyn Arts Council and contributions from readers. Learn more and support 3 Hole here.